Taken from notes for a talk at Harvard University on July 8, 2015 during an event in honor of poet Oleh Lysheha, who passed away on December 17, 2014.

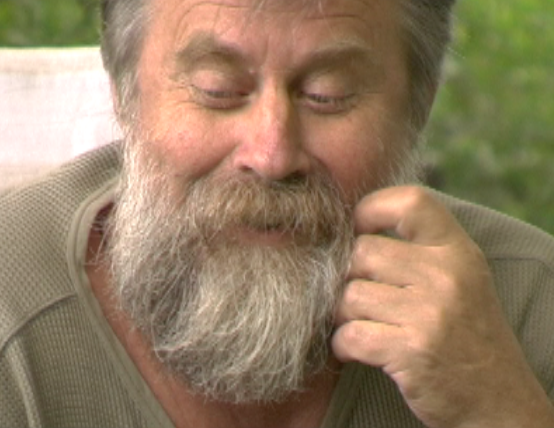

Oleh Lysheha discussing salt under a tree in Tysmenytsia, Ukraine, in 2012.

I first came across Oleh Lysheha's poetry at a Ukrainian bandura concert in New York City. On a table was a trim volume of poems with an abstract image on the cover, a red splatter that I later understood to be a swan. I opened the book and immediately my eyes lept from one apt phrase to another:

Does a hand know it? That it

Is barren land, hewed wood, mines crumbling?

What pain the heart must suffer --

To return again to the oil and salt,

To the native and stony ground,

I glanced to the top of the page. The poem was він, which is "He" in English.

"Apt" is really an understatement. At the time I had just returned from the Carpathian Mountains where I had begun production of a documentary film about an ancient salt mine, its innovative asthma clinic and its now on-going environmental catastrophe. My team and I conducted many technical interviews about salt-mine engineering, pulmonary medicine, speleotherapy and halotherapy. But I needed a poet to help us shed light on why humans need such sophisticated knowledge and industrial structure to handle salt. What was it about salt that made it so special? I needed someone who could open us to salt's spiritual and even magical qualities, a poet who could speak to the importance of salt for my film Salt in the Air. Wowed by Lysheha's exacting sensibility to nature, I was also grateful for my serendipity.

Oleh Lysheha at his home talking about axes in 2011. Tysmenytsia, Ukraine.

A brief backstory.

Salt in the Air is a portrait of Solotvyno, a small village in the Carpathian Mountains where an ancient salt mine doubles as a care center for asthmatics. Fascinated by the topic and by shimmering, almost ghostly images of the underground clinic, I went Ukraine in late 2010 only to discover that the mine was in horrific shape. In fact, it was collapsing and the Tysa River was flowing into it. The once picturesque mountain village and health spa was now filled with decaying steel mining towers and giant sinkholes into which homes and gardens and schools and churches had been engulfed. A creative person could potentially elevate the discussion and illuminate ideas that might span environmental catastrophe and the hope of medical innovation. At core, salt is the only mineral we eat in rock form and we cannot live without it. All life, as we know it, depends on salt. Though certainly impressive, it didn't feel like it was enough to say the mine was dying or asthma soothed. Salt demanded more.

So there I was in the East Village, awe struck by my luck and the words I had read. I contacted James Brasfield, Lysheha's English translator, who kindly connected me to Lysheha at his home in far away Tysmenytsia, a village surprisingly close to Solotvyno. On my next trip to Ukraine, I went to visit Oleh Lysheha.

Bilyk, Lysheha's dog, waiting for some borsch.

What a trip! What an adventure. Of our many evenings of discussion and engagement, one stands out. We had just finished a wonderful meal with Oleh's wife, Dariya, his sister, Lilia, and our cameraman, Andrej Yakovlev. As others prepared for bed, Oleh and I remained at the table, set to drink and talk late into the night.

Over the course of hours, Dariya would occasionally come into the room, trailed by the dog, Bilyk, and gently shame us or coax us to say goodnight. But we remained. Crickets began to chirp and owls hooted. The night grew quieter. Andrej, collapsing with exhaustion after a full day of filming, fell asleep in the corner with his hat over his face. And yet Oleh and I talked on, finally reaching a point of whispering to each other across the dinner table, the vodka half empty.

Suddenly, and to my great surprise, Oleh slammed his hands on the table, stood up and began to shout Hamlet at the top of his lungs. "To be or not to be!" Andrej sat bolt upright, rubbing his eyes and wondering what was happening. Dariya and Lilia burst into the room. Poor Bilik was barking himself senseless. And Oleh shouted on! He reached "....perchance to dream..." and then we were kicked out of the house. We didn't mind. We wandered into the backyard and over to his garden where he grew vegetables. There was a full moon under which we bobbed in and out of the light along rows of green peppers, potatoes and cucumbers, talking until about 3:00 in the morning. And then we went to bed. As I write these words, my thoughts feel like echoes of Lysheha's great poem Swan.

Oleh Lysheha at home in Tysmenytsia.

My God, I’m vanishing . .

This road won’t guide me anymore . .

I’m not so drunk . .

Moon, don’t go . .

I appear from behind a pine—you hide . .

I step into shadow—you appear . .

I run—already you are behind me . .

I stop—you’re gone . .

Only the dark pines . .

I hide behind a trunk—again, you’re alone . .

I am—you are elsewhere . .

Absent . .

Absent . .

I am . .

Elsewhere . .

All our days filming and getting to know Oleh were like this. Poetry seemed to be flooding the place. One day Oleh picked up a large stone. "It's a bird," he tells me. "An onyx. It's the flight of the Earth. Heavy." And then he looks at me with a wry smile. "Or a frog, of course." The wonder of the world captured in a riff.

Oleh was fond of Ezra Pound. He spoke often of his poetry, alongside the work of many English language poets. Robinson Jeffers. Henry David Thoreau. T.S. Eliot. On one occasion, Oleh picked up an axe and paraphrased Pound. "A new axe handle must be made with the old axe." I took this to be an expression of both tradition and the eternal forging of art and language. The timelessness of craft.

Timeliness or Timelessness

“When you breathe salt, you breathe in a small particle of the ocean. It gives you space inside yourself. You breathe vast space. You breathe fresh space and take inside freshness. Freshness. Just like a flower. You become a flower then. When breathing salt, you become a tiny, wild flower. That’s what we breathe it for. ”

Which brings me to the topic at hand: Timeliness or Timelessness. I had been struggling for some time over whether or not Salt in the Air should be a timely film or a timeless one. By timely I mean the sort of film that exposes the present, typically in a journalistic fashion, for the benefit or demise of the living. It's the kind of film that might play on an in-depth news channel or the type that has become common on the documentary circuit where human rights abuses or corruption are exposed. It's typically meant to incite action or inspire change of some kind, often from a left perspective politically, but not always. In the case of Solotvyno, there was plenty of corruption, cronyism, theft and otherwise sleazy business to make a timely doc. Vast corruption of this type, in fact, is what partly led to the Maidan Revolution just a few years later and sits as a significant underpinning for the current war between Ukraine and Russia.

Timelessness, on the other hand, is more focused on something that might resonate over generations. It's not just this particular crisis of 2010 during which a small mining town has been destroyed by greed and mismanagement. It's an investigation in what it means to be human. Why do we have salt mines in the first place? What do they represent? Salt is one of the few minerals we eat in raw form. We eat and breathe this crystal and our bodies are partly constructed of it. This is the timeless story and it's the one that Oleh offered to help me tell. We settled on timelessness and though I wonder if we got it right, we certainly picked the right path. It allowed Oleh to imagine a phrase like this:

When you breathe salt, you breathe in a small particle of the ocean. It gives you space inside yourself. You breathe vast space. You breathe fresh space and take inside freshness. Freshness. Just like a flower. You become a flower then. When breathing salt, you become a tiny, wild flower. That's what we breathe it for.

“What is most impressive about salt is that it’s a crystal. A pure crystal and it preserves everything in itself. It preserves memory and the feeling of time, space. Everything. Because it is crystal.”

Or this:

What is most impressive about salt is that it's a crystal. A pure crystal and it preserves everything in itself. It preserves memory and the feeling of time, space. Everything. Because it is crystal.

Fidelity to language became an important part of the filmmaking process, in part because of Oleh. I retained James Brasfield's elegant translations of Lysheha's poetry, including punctuation. Lysheha liked to use two periods after some lines. I asked him about this and he simply said, "Sometimes it's needed."

The Ukrainian title for Salt in the Air is Сіль у повітрі, a translation that Oleh crafted. But it could have been written Сіль в повітрі. Ostap Kin, the talented translator for Salt in the Air's subtitles, put it this way, "It's impossible to distinguish these titles in English. It's certainly clear in Ukrainian, but probably only for people dealing with letters and words (writers, editors, etc). In Ukrainian, if a word ends with consonant and the next word starts with consonant, and one needs to use a preposition in between, it should be a vowel " у" [u] ---> [Sil u povitri] in order to omit having three consonants in a row [Sil v povitri]. Also, the sound "v" in the word "povitria" makes it difficult to pronounce whole phrase, if one uses "в" [v] as a preposition."

Ostap's explanation probably feels too detailed for this essay. And yet precise language is often a deep and sometimes beguiling part of the craft of filmmaking. In the big picture I like to imagine that I am also crafting a new axe handle with the old axe. Now, in addition to being in front of the camera, Lysheha is present in the title of the film and he stays with me in my work as filmmaker. I feel the loss of his passing.

An old deer head mounted on Lysheha's wall in his home. For some reason, I felt a lot of affection for this run-down creature. What a strange beast.